RAPID DETERMINATION OF VIRUS ACTIVITY BY FLUORESCENT BACTERIA-IMPRINTED SENSOR

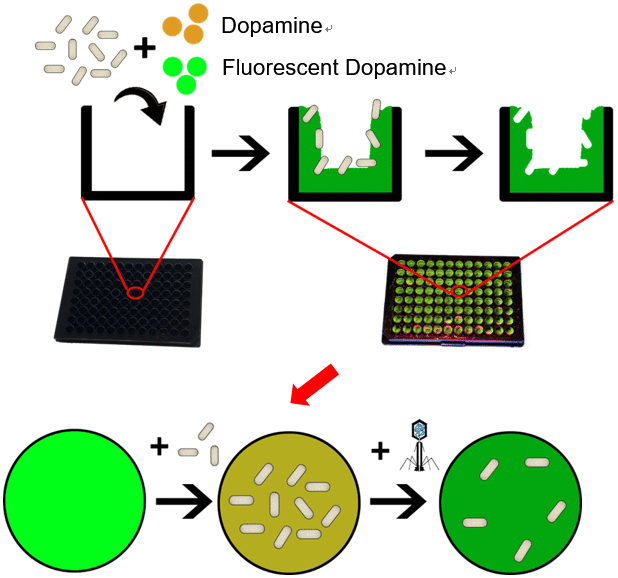

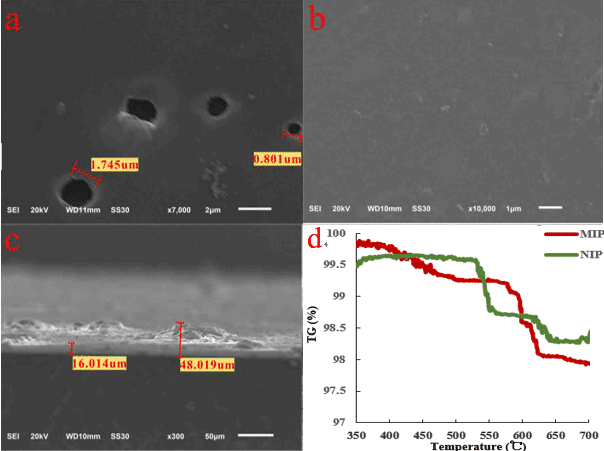

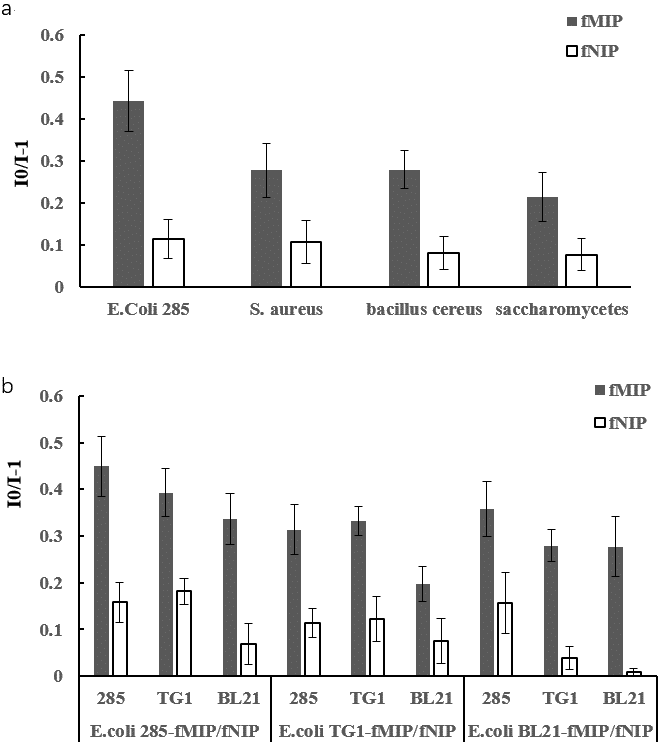

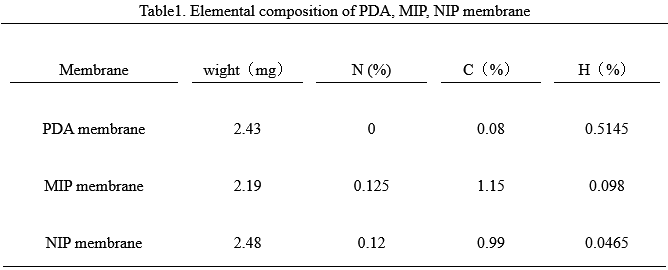

Rapid determination of virus activity is critical in preventing viral infection. Plaque-based assays are the standard methods used to determine virus activity and virus concentration in terms of infectious dose. Plaque-based assays need the culture of living host cells and the viruses to produce visible plaque, which is time consuming, laborious and need well-trained analysts. In this study, we first reported a rapid method to detect virus activity without the culture of host cells and viruses by using a fluorescent bacteria-imprinted sensor (Fig.1). Different bacteria-imprinted sensors were prepared on 96-well plate by self-polymerization of dansyl dopamine and dopamine in Tris-HCl buffer using different serotypes of escherichia coli (E. coli) as templates. The serotypes of E. coli included E. Coli 285,E. Coli TG1,E. Coli BL21. Elemental analysis(table1), scanning electron microscope (SEM, figs.2a-2c) and thermogravimetric analysis (TGA, fig.2d) confirmed the forming of bacteria-imprinted sites. Only living bacteria induced significant fluorescent quenching to the corresponding sensors. The sensors could distinguish different species of living bacteria in PBS buffer, but could not distinguish different serotypes of E. Coli (Fig.3).

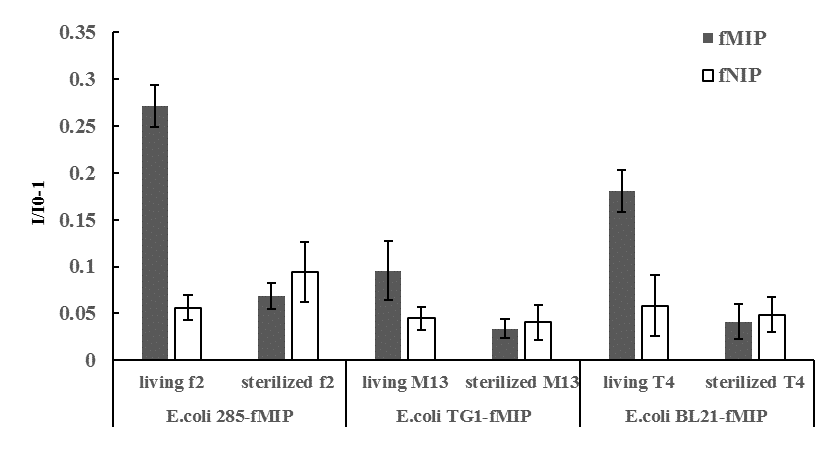

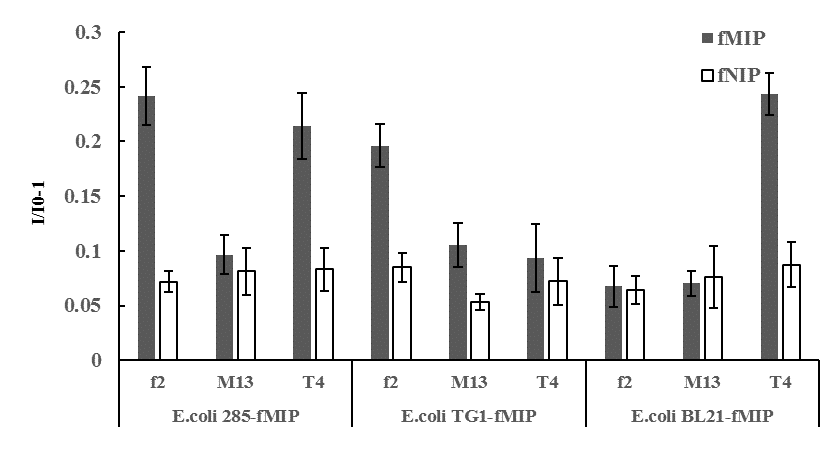

When different bacteria-imprinted sensors capturing living E. Coli were used to detect bacteriophages (bacteria viruses), only living phages could increase fluorescence intensity significantly after 2h incubation (Fig.4). Living bacteriophage could infect and lyse the captured host bacteria, which would free the imprinted sites and thus increase the fluorescent intensity. Dead (sterilized) phages could not induced significant fluorescence changes in all bacteria-imprinted sensors. Selectivity assay showed that one sensor could detect activity of one or several phages that could infect the captured living host bacteria. For example, sensor using E. Coli 285 as template could detect the activity of f2 phage (host cell E. Coli 285) and T4 phage (host cell E. Coli BL21) because both phages could infect E. Coli 285 (Fig.5). Compared to plaque forming assay, 108 PFU/mL f2 phage could be quantified by the E. Coli 285-imprinted sensor. The sensors developed in this work offer a new solution for rapid and sensitive determination of virus activity without long and complex culture procedures, which may have good applications in environmental monitoring, clinical diagnosis and food safety evaluation.

Fig.1 Schematic illustration of detecting virus activity using fluorescent bacteria-imprinted sensor

Fig.2 a) Surface SEM image of fMIP. b) Surface SEM image of fNIP. c) thickness of fMIP.d) thermogravimetric curve of MIP and NIP.

Fig.3 a) Fluorescence response of E. coli 258-imprinted sensor toward different microorganisms. b) Fluorescence response of different serotypes of E. coli sensors to different serotypes of E. coli (I0: fluorescence intensity before binding E. coli or other species of microorganisms; I: fluorescence intensity after binding E. coli or other species of microorganisms)

Fig.4 Fluorescence intensity change induced by living or sterilized (dead) bacteriophage (bacteria viruses) in corresponding bacteria-imprinted sensors. (I0: fluorescence intensity of before adding bacteriophage; I: fluorescence intensity after 2h of adding bacteriophage)

Fig.5 Fluorescence response of different E. coli-imprinted sensors toward different bacteriophages. (I0: fluorescence intensity of before adding bacteriophage; I: fluorescence intensity after 2h of adding bacteriophage)

Powered by Eventact EMS